In the chaotic aftermath of the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan last week, concerns are growing not only about the fate of the nation’s long-suffering peoples, but also for the country’s rich heritage.

Although 40 years of conflict often obscure Afghanistan’s significant Silk Road legacy and UNESCO World Heritage sites , the nation’s cultural monuments and intangible heritage are inexorably linked to its people.

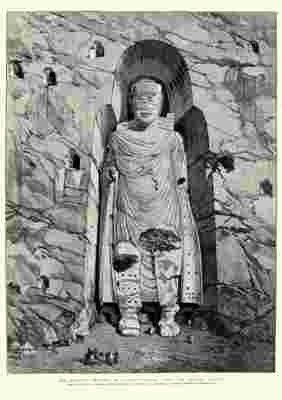

Now 20 years after then Taliban leader Mullah Omar sanctioned the destruction of the 6th Century Buddhas of Bamiyan , carved into a cliffside, the Taliban are back. According to local reports in Bamiyan, west of Kabul, this past Wednesday Taliban fighters blew up a statue of Abdul Ali Mazari, a leader of the Shiah Hazara minority long persecuted by the group, whom they executed in 1995. While the move was more about contemporary politics than the eradication of pre-Islamic heritage, it sent a chilling message to a captive civilian population.

Vintage engraving of a Buddha at Bamiyan

This past week, UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay issued a statement calling “for the preservation of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage in its diversity, in full respect of international law, and for taking all necessary precautions to spare and protect cultural heritage from damage and looting.”

Another statement issued by UNESCO’s Media Office in Paris said the organization is “closely following the situation on the ground and is committed to exercising all possible efforts to safeguard the invaluable cultural heritage of Afghanistan. Any damage or loss of cultural heritage will only have adverse consequences on the prospects for lasting peace and humanitarian relief for the people of Afghanistan.”

The statement also called for a “safe environment” for cultural heritage professionals and artists and expressed concern about “the impact of conflict on women and girls”, noting that, “Education is a fundamental human right.”

At the crossroads of Chinese, Indian, and European civilizations, Afghanistan was once better known for its wealth of cultural history stretching back 3,000 years, than its seemingly endless cycle of wars and invasions. In addition to the Buddhas of Bamiyan, the entire Bamiyan Valley is laden with ancient archeological remains, some of which were reportedly stolen from a warehouse this week by Taliban fighters . Although UNESCO has been supervising work in the area for several decades, it is unclear whether any of their staff are currently able to continue at this point, and as with many NGOs dealing with heritage preservation, news about evacuations and office closures have been suppressed for security reasons.

This is certainly the case with Turquoise Mountain , the NGO founded in 2006 by HRH Prince Charles and British academic, diplomat, explorer, soldier, and politician Rory Stewart, who wrote a book called The Places In Between chronicling his walk across Afghanistan. The NGO, whose stated mission is “to revive historic areas and traditional crafts, to provide jobs, skills, and a renewed sense of pride” is currently not releasing any information about its on-the-ground activities due to safety concerns for its staff. It is, however, actively fundraising for the communities it supports via its small business creating programs. Turquoise Mountain is also involved in the restoration of historic buildings including ones in Kabul’s old city , and it helps sustain traditional craft and jewellery workshops. A statement released with its crowdfunding effort says, “We are currently focused on emergency food and other supply distribution, healthcare services for children and families, and support for the individuals and communities for whom we are currently responsible.”

The Minaret of Jam

Fittingly for Afghanistan’s long history of both culture and conflict, the NGO is named after the lost city of Firozkoh, which is also known as Turquoise Mountain and served as the summer capital of the Ghurid dynasty, in the Ghor Province of central Afghanistan. Reputedly one of the greatest cities of its age, it was destroyed in 1223 after a siege by the son of Genghis Khan and then effectively lost to history. The Ghurid sultanate was built on the bones of the previous Ghaznavid dynasty. Ghurid leader Ala Al-Din Husayn burned their capital city, Ghazna, killing 60,000 inhabitants and imprisoned its remaining citizens using them to transport building supplies to Firozkoh and even, some claim, mixing their blood into mud bricks used for construction of the “Turquoise Mountain.”

The Minaret of Jam , said to be the lost city’s only remnant, is now on UNESCO’s list of endangered World Heritage sites. But the magnificent 12th-century monument, covered with geometric decoration and Kufic inscriptions in turquoise tiles, is likely more at risk from soil erosion than from the Taliban. Surrounding remains include stones with 12th-century Hebrew inscriptions and the whole site speaks to Afghanistan’s true spirit of pluralism, in contrast to the Taliban’s fundamentalist tradition.

Street life in front of the Herat's ancient citadel, which was restored by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Some 150 miles to the west of the Turquoise Mountain region is the old citadel of Herat, reportedly now occupied by the Taliban. Herat has been a recent restoration success story. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) has worked in the ancient crossroads city, home to Persians, Pushtuns, Uzbeks, Turkomans, Baluchs, and Hazaras, since 2005. The citadel, whose first iteration was built in the 4th century BC by Alexander The Great and has been destroyed and rebuilt several times, was saved from demolition in the 1950s and restored by UNESCO in the late 1970s.

The AKTC has committed a billion dollars to the restoration of over 150 heritage sites in Afghanistan, including Babur’s Garden , one of the earliest surviving Mughal gardens and final resting place of the first Mughal emperor, which has enjoyed 15 million visits over the past decade.

A small mosque in the Babur Gardens.

Heritage experts point to two decades of work by both Afghan and international archaeologists as another positive advancement in the protection of Afghan patrimony, including the development of the Afghan National Museum. The museum posted on their Facebook page on August 15 th that “Staff, artifacts, and goods are safe,” but noted that “continuation of this chaotic situation causes a huge concern about the safety of the museum’s artifacts.”

In the end it seems that the danger caused by the destabilization of the country and looting—which remained an issue over the past two decades even after the U.S. intervention in 2001—will prove a greater concern for Afghanistan’s rich cultural heritage than any threat from the Taliban. As the Afghan National Museum’s statement urged, “security forces, the international community, Taliban, and other influential parties” should “not let opportunists use this situation.”