From above, the cubic concrete structures that make up the newly expanded Glenstone Museum on 230 acres of rolling hills in Potomac, Maryland, could be mistaken as the remote compound of a well-funded cult. Only instead of an eccentric spiritual leader, it is the cult of art, architecture, and nature. That trifecta has found a harmonic convergence in the new Glenstone, which opens to the public on October 4 following a $200 million expansion.

Housing the world-class postwar and contemporary art collection of the Glenstone Foundation, established by billionaire industrialist Mitchell Rales and his wife, Emily Rales, a former art dealer who now serves as the museum’s director, Glenstone opens to the public on October 4 following a $200 million expansion begun in 2013. Originally founded in 2006 in a 30,000-square-foot building designed by Charles Gwathmey on 100 acres, Glenstone was highly restrictive about attendance, so few had heard of it and even fewer had seen it. (It’s most easily accessed by private vehicle but the public bus will begin making more stops at the museum next month.) But the recent expansion, designed by architect Thomas Phifer (founder of Thomas Phifer and Partners) in collaboration with Adam Greenspan and Peter Walker of PWP Landscape Architecture—adds a 204,000-square-foot museum building that is likely to catapult the collection into the ranks of the world’s most prestigious private institutions.

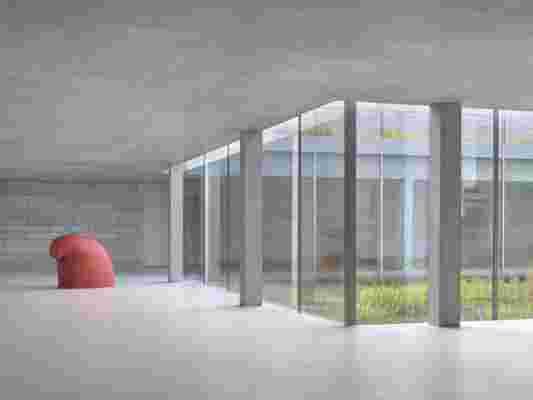

The Passage in the Pavilions, Martin Puryear, Big Phrygian , 2010–2014, painted red cedar, 58 x 40 x 76 inches (147 x 101 x 193 cm).

Its collection, which now numbers around 1,300 works, includes some of the biggest names in the 20th and 21st centuries, including Joseph Beuys, Louise Bourgeois, Willem De Kooning, David Hammons, Eva Hesse, Felix Gonzales-Torres, Bruce Nauman, Charles Ray, and Cy Twombly. It’s not the riskiest collection—the Raleses only buy works by artists who have at least 15 years of success behind them–but that doesn’t mean there aren’t some incredible surprises. In an outdoor room, for instance, the Raleses worked with Land Art powerhouse Michael Heizer to create Collapse , a giant square ditch with enormous steel beams poking out like pick-up sticks, which he designed in 1967 but never realized until now. They also worked with the sculptor Robert Gober to install a large room with six gushing faucets that was included in the artist’s 2014 MoMA retrospective.

The Raleses added 130 acres to the grounds and a 204,000-square-foot museum building, which is neatly divided into 11 galleries, many windowless, connected by a glass-walled walkway; that looks out onto an 18,000-square-foot “water court.” On a recent visit, clusters of lily pads and irises were giving way to fall as the reflection of gray skies on the dark watery surface gently illuminated the interior walkway.

Water Court at the Pavilions.

As Phifer’s elegant concrete structure settles into a sustainable meadow of native grasses, perennial flowers, and shimmering oaks—a swath of land that was once a fox hunting club and later home to Mitchell’s alpacas (which were relocated)—the only clue that the rural oasis was once subdivided to accommodate affluent suburban sprawl is a cluster of McMansions visible in the distance. But that vista will likely be shrouded one day when some of the 8,000 trees that were planted or relocated on the property mature over the next few decades.

Boardwalk at Glenstone.

Such is the long-term vision of the Raleses, who have conceived of Glenstone as a different kind of art space than most—one dedicated to the practice of “slow art.” As Emily explained to a crowd on hand last week: “We hope you slow down. That your pulse will also slow down. That you will start to become aware of your breath and the changing light in the galleries.” Rushing from work to work, or even worse, seeing everything quickly through a smartphone screen in the hunt for the most Instagrammable subject, is highly discouraged. The goal is for visitors to have a more intense, enriching, or enlightening experience. (The concept of Slow Art was first articulated in long form in Arden Reed’s book Slow Art: The Experience of Looking, Sacred Images to James Turrell (University of California Press: 2017).)

View into installation: Lygia Pape, Livro do Tempo I (Book of Time I) , 1961, mixed media on wood, 365 pieces, each 6¼ x 6¼ x 1½ inches (16 x 16 x 4 cm).

To that end, each work is surrounded by far more space than the typical museum experience affords—around 300 square feet—so viewers can easily see what they are looking at, and attendance is limited to 400 people a day. (Entry is free, although tickets must be reserved online in advance, and when the first three-month batch was released late September, they were snapped up in a mad rush—a scramble clearly at odds with the slow ethos.)

“The most challenging thing was to find an architecture that could have this slow experience,” said Thomas Phifer, who has designed numerous art spaces, including the North Carolina Museum of Art and the Corning Museum of Glass. In order to figure out what they wanted, the Ralses visited more than 50 museums and art spaces around the world, taking inspiration from a few places in particular, including Ryoanji, a Zen temple in Kyoto, Japan. While the thousands of cast-concrete blocks cladding the walls have a soothing, decorative effect, it’s the white-glass clerestories and skylights that are key, filling the spaces with incredibly soft, calming natural light. “You go from light to shade, to shadow—it’s a rich journey in light,” said Phifer. “I’ve never done anything like this.”

The Passage in the Pavilions, Roni Horn, Water Double, v. 3 (detail), 2013–2016, solid cast glass with as-cast surfaces, two units, each 50⅛ inches x 53–56-inch tapered diameter (127 cm x 135–142 cm tapered diameter).

As for the Raleses, the hope is to share their collection and sprawling property and the potentially uplifting, enlightening experience that art, architecture, and nature can provide with a far broader audience than was possible before. As Mitchell told the crowd: “It’s our gift to the world.”

RELATED: The Best-Designed Museum in Every State in America