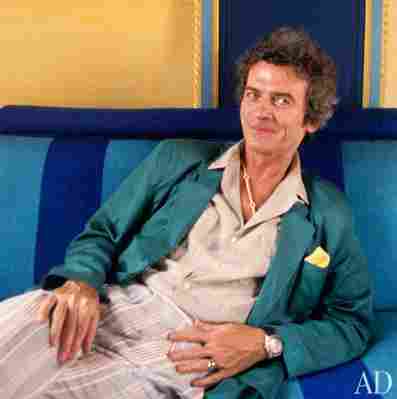

Americans with a creative bent sometimes thrive best far from their native land, finding true freedom of expression only after abandoning the land of the free. One such adventuresome expat was Bill Willis (1937–2009), the lanky, cranky, often pharmacologically fueled interior designer to Morocco’s fête set for nearly 40 years.

Americans with a creative bent sometimes thrive best far from their native land, finding true freedom of expression only after abandoning the land of the free. One such adventuresome expat was Bill Willis (1937–2009), the lanky, cranky, often pharmacologically fueled interior designer to Morocco’s fête set for nearly 40 years. Born in Tennessee, educated at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and briefly a resident of Rome—he once operated an antiques shop near the Spanish Steps—Willis found a foothold in North Africa in the mid-1960s and never left. “My discovery of the Islamic world has been an astounding experience,” Willis told Architectural Digest in 1989, during the heyday of his reign as the king of latter-day Orientalism, a pan-Arabic hodgepodge whose hallucinatory special effects provided a perfect background for living the louche life.

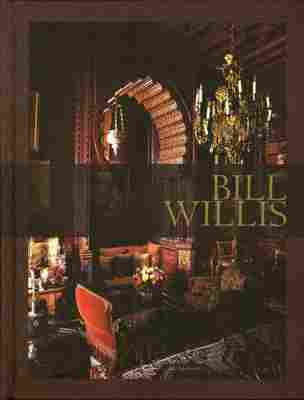

When Willis wasn’t snorting cocaine (“the only drug I really like,” he once noted) with the Rolling Stones, munching hashish cookies with the writer William Burroughs, or dropping acid with the lingerie designer Fernando Sanchez somewhere in the Moroccan desert, he created rooms so romantically over the top that they recall tales told by Scheherazade. Constants in his design vocabulary included flamboyant tiles, billowing domes, majestic fireplaces, and the softly polished waterproof plaster known as tadelakt, typically used in public bathhouses. (In fact, Willis set off a tadelakt craze that some observers, me included, wish would abate just a bit.) Those artisanal leitmotifs are evident in the lushly illustrated new book Bill Willis (Éditions Jardin Majorelle), authored by American design writer and editor Marian McEvoy. It is the first monograph devoted to Willis’s limited yet influential oeuvre, which was rarely seen in American magazines—two exceptions being the projects originally published in AD and reproduced here.

Working with Paris-based photographer Nicolas Mathéus, McEvoy spent around five years tracking down 15 of the finest surviving Willis commissions, styling them to look their best, and then recording them, inside and out. Especially challenging, she says, was convincing her irascible, often bibulous subject to open up about his colorful life. “Bill was a difficult fellow, not a Chatty Cathy, and a raging snob, too—but with a marvelous sense of humor,” McEvoy recounts, adding that when the designer was in good spirits he would regale her with tragic family tales straight out of a Tennessee Williams melodrama. “Though he did have a pretty positive opinion of himself, he was not a braggart,” she adds. “He was not interested in going down memory lane.”

The 262-page volume is an elegant tribute to the master’s opulent style, charting a career that took off after he restored a dilapidated 18th-century palace in Marrakech’s medina for two hedonistic pals, American oil heir J. Paul Getty, Jr., and his Java-born bride, Talitha. (“We all moved in to live a kind of dolce vita,” Willis told AD, though the counterculture languor soured a few years later, when Talitha Getty succumbed to an overdose of heroin.) One of the designer’s last productions, for Italian style icon Marella Agnelli, was a stately garden pavilion that overlooks a shimmering lily pond at her estate in the Palmeraie oasis, on the outskirts of Marrakech.

Willis may have been a passionate Arabophile and counted the Alhambra among his stylistic influences yet he was no antiquarian stickler. The kitchen of his own house, for instance, was plastered with tadelakt unexpectedly expressed in wide stripes of pale jade-green alternating with an otherworldly orange. “Bill took the textures and shapes associated with Morocco and tweaked them to look more Western,” McEvoy explains. “He imposed his own colors on the tile makers, and he wasn’t nuts about gebs, that white honeycomb plasterwork, and used it sparingly. He didn’t like anything mingy, delicate, sweet, or cute. His rooms were always handsome and masculine. He didn’t do frilly.”

In addition to featuring Willis’s mansions for seasonal Marrakchis such as society figure Marie-Hélène de Rothschild and fashion-world power couple Pierre Bergé and the late Yves Saint Laurent (their Paris-based foundation funded the book’s publication), McEvoy takes readers on a visual tour of several of the designer’s evocative public commissions, namely Hotel Tichka and restaurants Dar Yacout and La Trattoria (all three in Marrakech) and Rick’s Café (in Casablanca).

Willis’s own residence, Dar Noujoum, a rambling riad that was once a royal harem, is the book’s star turn, and it is arguably the purest expression of what could be called le style Bill. Featured in AD in 1989, its lofty, sandalwood-scented rooms were jam-packed with Afghan embroideries, gigantic suede poufs, Moroccan vases, and tile-topped opium tables, the tadelakt walls set gently aglow by dozens of sputtering candles. It was a magical, slightly grimy setting I was lucky enough to experience one evening not long after my husband and I moved to Marrakech in December 2003. New friends took us to Willis’s place for drinks, and I remember well our rail-thin host, dressed in an embroidered robe, his eyes smudged with kohl, angrily barking orders at one of his maids, who responded in furious kind.

Bohemian atmospherics aside, “Bill was no hippie,” McEvoy observes of the Memphis-born expat who made Moroccan style chic. “He was like an 18th-century grandee—he lived big.” Until illness and alcohol brought his career to a standstill, Willis ensured that his clients did too.

At present, Bill Willis is sold exclusively by the shop at the Jardin Majorelle in Marrakech ( jardinmajorelleom ). It is available in two editions—one with a fabric-covered slipcase (1,300 dirhams, or approximately $153) and one without (800 dirhams; $94). This summer the book will be stocked at the boutique of the Fondation Pierre Bergé–Yves Saint Laurent in Paris. For information, contact editions@jardinmajorelleom .