This is the inaugural post for my regular column on Daily AD. We’re calling it The Aesthete, a nod to my personal blog, An Aesthete’s Lament, which I maintained from 2008 until recently. As I did in that space, I will cover a broad range of topics and personalities from the worlds of interior decoration, architecture, art, and fashion—exploring the nooks and crannies of design history with an idiosyncratic eye. It will be about roads less traveled and, most of all, about inspiration.

This is the inaugural post for my regular column on Daily AD. We’re calling it The Aesthete, a nod to my personal blog, An Aesthete’s Lament, which I maintained from 2008 until recently. As I did in that space, I will cover a broad range of topics and personalities from the worlds of interior decoration, architecture, art, and fashion—exploring the nooks and crannies of design history with an idiosyncratic eye. It will be about roads less traveled and, most of all, about inspiration.

To start, I thought I’d head to Morocco, where I traveled recently and where I was lucky enough to live for a few years with my family. During my time there, in Marrakech, I developed a deep fondness for a number of aspects of the culture—the couscous, the call-to-prayer wail of the muezzins, and especially the intricate geometric patterns one sees everywhere in the architecture and decorative arts. Indeed, such patterns can be found throughout the Islamic world, whether executed in carved wood, chiseled stone, or polychrome tiles.

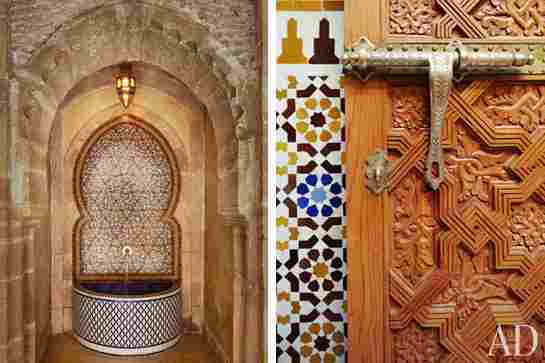

Abundant examples of this type of decoration can be found throughout the Moroccan residence of Manhattan art dealer Dorothea McKenna Elkon and her husband, designer Salem Grassi , which I wrote about in the May issue of AD. Kaleidoscopic extravagances that resemble interlocking stars enliven every corner of the three-story riad the couple calls Dar Maktoub (House of Destiny), from wall fountains with tilework known as zellige to vaulted and coffered cedar ceilings.

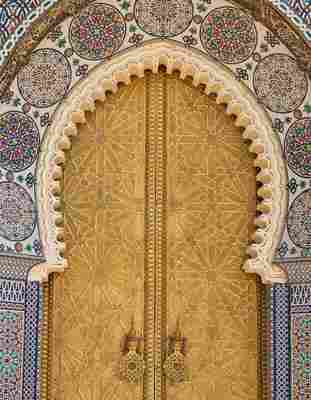

“Only in Islamic countries, and in particular Morocco and Andalusia, has geometric decoration taken on such importance,” writes Jean-Marc Castéra in Arabesques: Decorative Art in Morocco (ACR, 1999). Precisely why geometric patterns became so central in Islamic decoration remains unclear. The most enduring explanation is that they began to be used a millennium ago as a way to conform to religious strictures widely interpreted as forbidding the depiction of the human form, which might be seen as man’s attempt to compete with God’s genius. As My Marrakesh 's Maryam Montague notes in her new book, Marrakesh by Design (Artisan), an ancient Islamic edict states, “Painters will be among those whom God will punish most severely on the Judgment Day for imitating creation.” With such a potential fate in store, it’s no wonder that stars, octagons, and the like—along with sinuous, vinelike motifs and calligraphy—became the vocabulary of choice in the architectural circles of the Islamic world.

But that’s not the whole story. Geometric patterns, other Islamic art specialists have suggested, served important symbolic functions. “The proliferation of arabesque abstract decoration enhances a quality that could only be attributed to God, namely, His irrational infinity,” scholar Wijdan Ali observes in The Arab Contribution to Islamic Art (the American University in Cairo Press, 1999). “The pattern of the arabesque, without a beginning or an end, portrays this sense of infinity, and is the best means to describe in art the doctrine of tawhid, or Divine Unity.” (Tawhid seems to have a social dimension, too, since many Moroccans refer to beloved friends as sister or brother, son or daughter, whether or not they are actually related.) Indeed the eight-pointed star, formed by two overlapping squares, is the basis of many patterns seen across Morocco executed in every possible material—from the tiled graves at the Saadian Tombs in Marrakech to the carved-plaster arches in the throne room of the Royal Palace in Rabat to the brass door knockers found in hardware stores everywhere in North Africa. Still more complicated stars are seen, including rare examples featuring an astounding 96 points.

Given the complexity of these starry patterns, some scholars have attempted to link them to mathematics that originated in Arab culture, especially its pioneering exploration of algebra and trigonometry. “There is a fantastic book called The Sense of Unity that covers everything you want to know about the importance of numerology in Arab culture,” says Achva Benzinberg Stein, an award-winning landscape architect who designed the flamboyantly tiled Moroccan courtyard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recently reopened galleries for Islamic art; she also wrote Morocco: Courtyards and Gardens (Monacelli Press, 2007). Geometric patterns, Stein continues, also embody “the idea of negative and positive space, just like in the Tao. Most people don’t see these patterns in that way, but for every negative there is a positive. You start at a point and extend it, top to bottom.”

Repeated over and over again, seemingly exponentially, these geometric patterns—whether quietly monochromatic or richly polychrome—seem to inspire a sense of cosmic harmony. The sensory experience is not unlike listening to a performance of Ravel’s “Boléro,” a musical composition that was derived from a Spanish dance (likely Moorish in origin) and that repeats the same rhythm and melody, over and over, for 17 increasingly hypnotic minutes. The relentless rhythms of the Arab world’s interlaced starbursts, repeated ad infinitum, seem perfectly suited to houses like the one created by Elkon and Grassi in the heart of Essaouira’s medina: a retreat for a couple and their friends to unwind. Those patterns are also eloquent reminders of how in this high-tech age, exquisite handcraft continues to enrich the world around us.