“Studio 54 is one of those stories that everyone thinks they know, but they don’t really know,” says film director, producer, and journalist Matt Tyrnauer ( Valentino: The Last Emperor, Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood ). “For me that’s a great starting point for a documentary.” Tyrnauer, a onetime editor at *Vanity Fair, took on the tremendous responsibility of telling the legendary yet short-lived discotheque’s tale of an epic rise and fall in his new documentary, Studio 54, premiering October 5. Plenty of glittering archival images of Diana Ross, Liza Minnelli, Michael Jackson (quoted calling it “really escapism…you go wild”), Andy Warhol, and Bianca Jagger dance across the screen over course of its 95 minutes, but one of the surprise stars of the saga is Studio’s design.

Realize it or not, the nightclub where the velvet rope was born (in all its controversial glory) signals a turning point in after-dark aesthetics, and forecast the now ubiquitous concept of experiential design. When Ian Schrager and the late Steve Rubell, lower-middle-class college buddies from Brooklyn, conceived it in 1977, Schrager was green—and a lawyer. Today he’s credited with creating the concept of a boutique hotel, and is the hotelier and real estate developer behind Edition Hotels and Public Hotel, among others, working with the likes of designer Philippe Starck.

The dramatic entrance hallway—a leftover from the space’s time as a theater—during an annual refurbishment.

Yet distinctiveness is something Schrager identified early on as being critical to success. Whatever the project, “It’s always meant to have a visceral impact on the person,” he says. Tyrnauer, who shared a love of design with Schrager before making the film, says, “Ian turns out to be an intuitive architectural and design genius. Part of the story I tell is about Mr. Inside (Ian) and Mr. Outside (Steve) and characters with those attributes coming together to form the perfect team. Ian’s extraordinary flair for design and his incredible native talent and ability to innovative drove the Studio 54 aesthetic, and Steve’s people skills [kept] the club populated with the most glamorous mix of jet set and New York society of the moment.”

With Studio, “we were trying to generate a combustible energy, explosive—a mayhem for people to have fun,” says Schrager of their simple yet groundbreaking modus operandi. As seen in the documentary, the setting was perhaps the most important element. The seedy location—the former Gallo Theater (circa 1927) and CBS studio ( What’s My Line was filmed there)—couldn’t have been more ripe for action. “The adaptive reuse of the theater ends up being very significant,” says Tyrnauer.

The bar, banquets, and dance floor of Studio 54 after hours, with the balcony overlooking it all.

Permits be dammed, the twin masterminds went for it with unbridled energy, spending just six weeks with a team comprising architects Scott Bromley and Ron Dowd, Tony-winning lighting designers Jules Fisher and Paul Morantz, set designer Richie Williamson, and $65-a-day workers to black out the doors, level the floor, build a disco booth, and construct a dance floor as well as extensive sets that transported disco fans to a realm that felt wild, free, and safe. Low sofas, claret walls, silver vinyl–covered floating platforms, mirrors for days, massive bars of light, and a balcony with bolsters (and binoculars) on which weary dancers could collapse or voyeurs could watch the action below—these were never-before-seen elements for nightclubs, which in those days were basic black boxes with a DJ handling not only music but also lights. Tyrnauer reveals they met many constraints, but “sometimes having limitations causes innovation, and in this case that is surely true.”

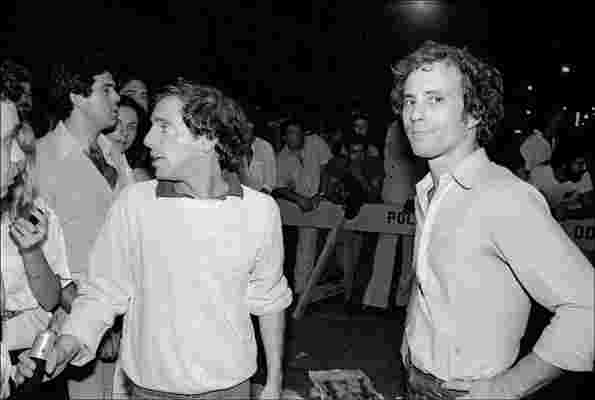

Ian Schrager (right) and Steve Rubell outside Studio 54.

Schrager and Rubell went far beyond flashy lighting schemes. Using left-behind rigging, they emitted or dropped fog, wind, snow, sunrises, sunsets, and tornados, not to mention streamers, balloons, and even little gifts on the 2,000 dancers below. “The level of expectation was an assault on the senses and made everyone’s heart beat a little faster,” says Schrager of the special effects. “I think it was a catalyst caused by other elements as well, including the design of the space…up to that point there was never an effort made to make the design flexible and fluid. This all worked together and made people let their hair down and have a great time.”

The infamous light-up Moon and the Spoon installation—depicting a giant cocaine spoon traveling to the nose of the man on the moon—features on the back wall of the dance floor.

Their triumph was in the perfect alchemy, and the duo kept the magical alive with annual renovations during the three years they owned the club. “In order to keep people excited and continue to always keep them guessing what would be coming next, we kept updating the visuals and the set, perhaps made it more sophisticated and refined to keep it fresh and relevant,” says Schrager. The original rich reds and golds playing into the Baroque look of the old theater became increasingly stripped-down and mod as the ’70s came to a close. Even in the midst of serious legal investigations and battles they spent $1.5 million—almost three times the initial cost—on a Sweeney Todd–inspired moving bridge, among other updates. “They were trying to put the best face on what they knew was an increasingly desperate situation,” says Tyrnauer.

The view from the DJ booth looking up toward the crowded balcony.

This theatrical social experiment was a success down to the very last party they threw before—spoiler alert!—going to prison (President Obama fully pardoned Schrager). “I think this is the architecture of voyeurism, actually,” says Tyrnauer. “You could loom over and spy on dancing, and I think that was part of the thrill of Studio for a lot of people. Andy Warhol wasn’t on the dance floor once, but it suited him beautifully. It was a space that provided something for every proclivity.” Decades later the discotheque’s influence is still felt far and wide, according to the director. “There’s no question that hotels like Delano and Royalton utterly redefined interior design not only in hospitality but across the board, and I think all that innovation and paradigm shift in public design has its origins with Studio and Ian Schrager.”

RELATED: Go Inside the Most Iconic Nightclubs in History