View Slideshow

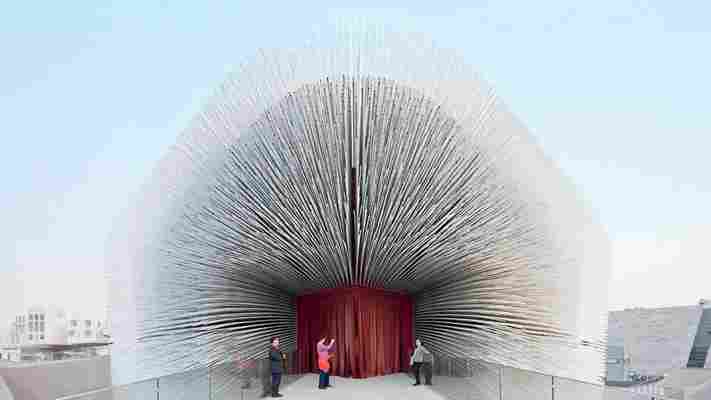

Thomas Heatherwick doesn’t do ordinary. Commissioned to design a pedestrian bridge in his home city of London, he built a structure that rolls into a wheel to make way for passing boats. For a Longchamp boutique in New York, he fashioned a curvaceous 55-ton staircase with fabriclike glass balustrades. And amid the dizzying array of pavilions at Shanghai’s Expo 2010, his Seed Cathedral stole the show—its bristling 60,000 seed-tipped optical rods gently swaying in the wind. Already known as an innovator in the design world, the 42-year-old Royal College of Art graduate is due to reach even greater heights this spring. His studio’s work will be the subject of a Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition opening in late May (with an accompanying monograph from the Monacelli Press), just as his reimagined version of London’s double-decker bus starts to fill the city’s streets. And at the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony—an extravaganza directed by Danny Boyle—it will be a Heatherwick-designed cauldron holding the flame aloft .

Architectural Digest: Though you trained as a designer, not an architect, the scale of your projects has increased in recent years. How has working big changed your thinking?

Thomas Heatherwick: I am finally getting the chance to build large structures and break preconceptions that my designs are just sculptures for people to be in. But my work always comes down to the human scale. I’m really interested in how you think strategically—do large-scale planning but also stay sensitized to ambience and creating spaces that human beings feel comfortable in. A client we’re working with has employed some very well-known international architects and said, “They do the big; they don’t do the small.” So we’ve taken that on as a bit of a challenge.

AD: You’re also very interested in infrastructure—bridges, power stations, parking lots—not necessarily the most glamorous of projects.

TH: I suppose I perceive it as glamorous to take something that we are used to having such low ambitions for, like a car park, and make it special. Whereas if you’re asked to take on an art gallery? Yeah, right! How do you make an amazing art gallery? However creative the design is, something inside me groans. I have a strong sense that every project is an invention, which is not a word I hear being used in architecture courses.

AD: Many people would say that what you do is re invent. Your update of the London bus, for example, recasts an icon that people love.

TH: I felt there was a lot to do to improve it. People love the idea of the bus, but it is experiential mayhem. And there were successful things from the older [designs] that we reintroduced. The calmness of the bench seats, for instance. That was a good idea—why did we throw it away?

AD: For your extruded-aluminum benches, which were recently exhibited at New York City’s Haunch of Venison gallery, you’re working with a factory that produces parts for China’s space program.

TH: Yes, and they’ve been very accommodating. We’ve extruded lengths specifically for different clients—and I really like the stopping-and-starting bits, where you see how 10,000 tons of pressure forces the aluminum to contort. We saw it as a way of testing out an idea—an industrial experiment. The benches are dying to be airport seating, but at the moment there’s only one machine on the planet that can make them. So there’s no economy of scale.

AD: Are your creations playful? I’m thinking of the Spun chair, which rocks in 360 degrees, or the Seed Cathedral—which looks like a hairy building.

TH: I suppose the question is, Is my studio’s work playful or is everyone else’s work too serious? And actually, the Seed Cathedral was serious. With 60,000 varieties of seeds, it was the most biodiverse thing in Shanghai, or in the whole region. There were no crazy colors. When things look like they’re trying to be fun, I have a slight wariness— it’s fun, kids! I’m interested in how you underpin things with a kind of gravity. If you manage that gravity, your designs can be as light as you want.

Click here to see examples of Thomas Heatherwick’s cutting-edge designs.