When the Whitney Museum of American Art unveils its new downtown Manhattan home on May 1, it will mark the culmination of more than a decade’s worth of work by the building’s architect, Renzo Piano. Originally tapped to expand the Whitney’s longtime Marcel Breuer–designed location on the Upper East Side, the Italian Pritzker Prize winner crafted an entirely new edifice after the institution opted to move to a prime plot overlooking the Hudson River at the south end of the popular High Line park. As visitors will discover, Piano’s much-anticipated creation is a game changer for the museum, providing the large, adaptable interiors it had craved, with roughly twice the exhibition space of the Breuer building and more than 220,000 square feet in total. But the move also gives the Whitney a fresh identity, placing it in the fray of the city’s buzziest neighborhood for 21st-century art and architecture.

“We weren’t just creating a shelter for art. We also had to consider the symbolic value that a project like this will have for generations,” Piano says. “It was necessary to be brave, to express the strength of a museum for American art, which by definition resonates with ideas of freedom.”

Certainly Piano knows a thing or two about balancing all that. Over the last half-century, he has completed some two dozen museum projects—from the 1977 Centre Pompidou in Paris (conceived with his then-partner, Richard Rogers) to the 1986 Menil Collection in Houston to the revamped Harvard Art Museums, which debuted in Cambridge, Massachusetts, this past November. Along the way he and his studio, Renzo Piano Building Workshop, have earned a reputation for conjuring flexible light-filled spaces that offer ideal conditions for exhibiting art.

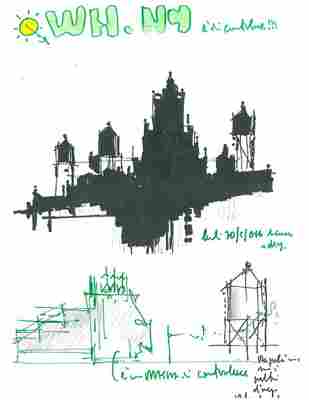

His scheme for the Whitney, asserts its director, Adam D. Weinberg, “is the best of Renzo, a mix between the contemplative, human scale of the Menil and the machinelike characterof the Pompidou.” An industrial swagger comes across upon first laying eyes on the new building, its no-nonsense exterior—clad in panels of enameled steel—nodding to the erstwhile abattoirs and warehouses of the surrounding Meatpacking District.

Piano finessed the overall form to reflect the program inside, with the galleries andoffices divided into separate volumes. On the building’s southern side, exhibition floors of gradually smaller size occupy stories five through eight, yielding stepped levels with terraces that will showcase alfresco art. (Visitors can move between them using a series of outdoor staircases.) The northern half, meanwhile, comprises administrative and curatorial areas as well as secondary spaces, among them a study center for works on paper. The latter, like the classrooms and170-seat theater on thethird floor, is a first for the museum.

“This building is not some crazy dancing elephant,” Piano jokes of the understated structure, which was realized in collaboration with the Manhattan firm Cooper, Robertson & Partners. But design, he is quick to add, “is not simply the consequence of objective circumstances. You have to shape them.”

Nowhere is that sculpting more finely tuned than at street level, where Piano carved out a large section of the first floor to create an 8,500-square-foot plaza (an area that will no doubt draw substantial foot traffic thanks to its proximity to the High Line). Window walls establish a sense of openness between it and the lobby, which, in addition to a gift shop and a Danny Meyer–helmed restaurant, features a gallery that’s free to the public. This subtle pedestrian-friendly transition, Piano says, “is a celebration of the museum’s accessibility.”

Visitors ascend to the main galleries via a central staircase or one of four elevators with interiors devised by the late artist Richard Artschwager. Most impressive is the fifth floor’s showstopping 18,000-square-foot space, the largest column-free museum gallery in New York City. Making it all the more remarkable are broad windows that frame panoramas of the Hudson River to the west and the city skyline to the east. In this room, as throughout the exhibition areas, floors of reclaimed pine offer a warm complement to the stark construction.

In total the Whitney now boasts more than 60,000 square feet of indoor and outdoor exhibition space, all of which will be filled with pieces from the museum’s permanent collection for its inaugural show. Surveys of Archibald Motley and Frank Stella will follow, but a comprehensive display of the museum’s 21,000-plus works will remain on view (far more than the Breuer building ever allowed). Says Weinberg, “People who come for the Rothkos, the Calders—these pieces will always be there.”

For the Whitney’s staff, the new building enables them to work together under one roof for the first time. “No one will be more than 50 feet from the art,” the director notes. Of course for one key team member, the job is nearly done. “I don’t know what it’s going to be like not to work with Renzo,” Weinberg says. “We’ve been collaborating for almost 11 years.” As Piano wraps up the project, he does so with a sense of satisfaction. Says the architect, succinctly, “Here, the Whitney can better celebrate what it truly is.”

whitnerg and rpbom