It’s as if Adam Richards has seen hundreds of years into the future, to a potentially post-apocalyptic time, and planned how his house, Nithurst Farm, will look as a ruin. It is a stepped three-story structure, made of concrete and wrapped in brick. You approach it from above, driving down the hill: Windows peek out beneath their arched brick veils on the east and west faces; a double chimney rises out the top story; it resembles a tugboat setting sail, southwards (and away from London).

The arches draw attention to the fact there are two separate layers to the house: The gap between the concrete and the brick both protects the concrete from moody English weather and forms an insulation gap—last Christmas, the gas ran out, but the house stayed warm for three days.

The driveway winds around the house, depositing you in the farmyard, facing the entrance on a cut-corner of the house. The farmhouse cottage that used to sit here faced this way too—Richards and his wife, Jessica, rented the now-demolished cottage for five years (initially coming on weekends), then bought it and moved in when Jessica was pregnant with their second child. Expanding the cottage wouldn’t work, so down went the 150-year-old structure. In its honor, its replacement had to last hundreds more.

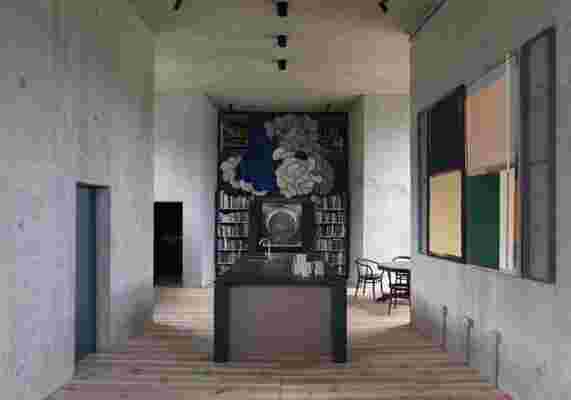

On the wall to the right is a four-panel artwork, Aperture Painting; Part Of Some Of by Helen A. Pritchard. The slate island benchtop was formerly a billiards table, and behind it is an artwork entitled Clouds by Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec.

Walking in, you are hit by the scent of the logs piled along the wall of the teensy antechamber. It’s dark, too, culling your sense of sight, heightening the others. The room compresses its transients before releasing you into the great hall. This is the main space on the ground floor, an expansive room with almost-15-foot-high ceilings. Here you really see (and feel) the bare faces of the concrete, pockmarks and all. There are six towers, as such, embedded—study, laundry room, larder, washroom, and ascending stairs, stashed within. Richards looked back to before the time of the open plan, to medieval great halls and town squares, the towers emptying into the space, like Palladio’s Villa Barbaro, and pay homage to architect Tadao Ando. The house is tapered, too, the false perspective making it feel longer; the concrete slabs and wooden boards meet in the centerline, the ceiling looks bowed, vaulted, like a church.

Architect Adam Richards.

“I’m interested in pulling together cultural ideas that help to tell a story,” says Richards. “On one level, Tarkovsky’s movie Stalker is about finding a home for ourselves in the world, and the journey that his characters go on in this quest. Our house too carries a journey within it—horizontally and vertically.” For Richards’s “room,” it means directing you to the verdant landscape outside. The east wall facing the road is windowless, draped with centuries-old tapestry fragments. In front hang screen prints of Robert Mangold’s Geometric compositions, eight out of nine displayed in a two-by-four formation. The final, missing member is funnily the most important: a three-stepped figure, it inspired the house’s structure; Richards hasn’t found a place for it yet.

Richards designed the kitchen so that there wouldn’t be any hanging cupboards—ample storage is provided under the island. To the right is the larder, which has no door. “My wife seldom closes doors,” Richards says as justification.

The other focal point of the sitting room is Simon Norfolk’s photo of the Large Hadron Collider. Richards actually designed the room around it, but hadn’t even bought the photo yet—he only knew it existed. It sits dead-center, playing with the sun in the daytime, and the fire at night.

Here, 16th- and 17th-century tapestry fragments hang on the eastern wall of the sitting room. Richards likens this wall to being in the back of the cave. “I think somewhere in the back of our minds, we’re still in a cave,” he says.

Outside, the house bends into itself because of the taper, embracing the lawn. This side of the house, Richards says, is about stillness. The nature, the birds, the many trees.

Going up the stairs, which Richards calls the house’s “subconscious mind,” you reach the living quarters, consisting of five bedrooms: two guest rooms with descendant en suites (suspended above the ground floor’s bathroom and study, in the towers), two bedrooms occupied by their three children (the two boys share, for now), and a spare.

The window grid on the south face was inspired by Paul Nash’s painting Mansions of the Dead. It was only when drawing it out that Richards noticed he’d drawn a large hashtag, which he then leaned into by layering Wienerberger Pagus Grey bricks on, to mimic the header bricks found on the farm’s other buildings. Staring down the center is the Simon Norfolk’s Untitled (Large Hadron Collider No. 2).

Richards’s father was a pilot and died in a plane crash, so the movie A Matter of Life and Death resonated. He always wanted to work it into his house, resulting in the “stairway to heaven”: Open up the double doors and sunlight shoots down, into your retinas. At the top is a commission by Jane Edden of a miniature jacket made from feathers, the accompanying tag bearing his dad’s final flight details.

The master suite is, like the rest of the house, split down the middle: On each side, his-and-hers beds (Richards wife says he snores), wardrobes and sinks (good sense). A bath sits facing the north, as does the shower, which has unobstructed views, allowing husband and wife to enjoy the best views from the house in their privacy.

The ultimate resource for design industry professionals, brought to you by the editors of Architectural Digest

While it seems a lot of Richards’s inspirations are to do with rebirth and heaven, he’s more interested in this life. His fascination with ruins is to do with “the persistence of ideas.” Without the people, the furnishings, the detritus of our lives, the house still makes you feel.