To borrow a line from the cinema jargon that Los Angeles thrives on, the making of L.A. is an epic affair. Since the city’s growth in the 1880s, modern L.A. has had its fair share of plot points—from the Roaring Twenties and the rise of Hollywood, through the Great Depression, all the way to WWII and the post-war housing crisis of 1946 that followed. At that time, the city’s architectural scene was defined by the likes of Albert Martin, Welton Becket, and William Pereira, but one architect whose lesser-known career tracks modern L.A.’s entire history is the subject of a compelling new documentary: Paul R. Williams.

“He really grows up with the city,” says Christopher Hawthorne, the city’s chief design officer and former Los Angeles Times architecture critic. Hawthorne took part in telling Williams’s story in a recent documentary from PBS, titled Hollywood’s Architect: The Paul R. Williams Story, which is available to stream now . A prolific architect whose career spans over five decades and includes more than 3,000 buildings in Southern California, Paul R. Williams was the first African American certified architect on the West Coast, and the first African American admitted to the AIA.

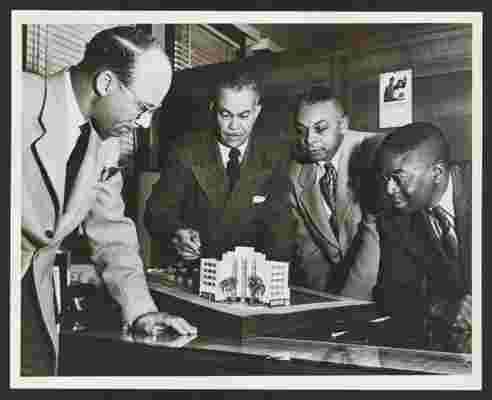

Paul Williams, second from left, with a model of Golden State Building.

Nicknamed “architect to the stars,” he had a special relationship with the silver screen. “He really made popular and accessible a certain idea of Hollywood glamour through residential architecture,” says Hawthorne. In a way, Hollywood and Williams’s career developed hand in hand. Synonymous with leisure and luxury, Hollywood became a cultural icon with its own set of rules—and Williams became one of the most sought-after architects in an industry captivated by fantasy and opulence.

After he made his Hollywood debut designing an Italian Revival–style mansion for silent film star Lon Chaney, Williams went on to design a reel of lavish residences for Hollywood stars including Lucille Ball, Cary Grant, and Tyrone Power. In 1956 he gained national exposure with his design of Frank Sinatra’s sensational Beverly Hills midcentury-modern residence (which was unfortunately torn down in 2006). “He was working with a lot of clients who were used to reimagining the world on a daily basis in their work,” says Hawthorne. “His houses were very charismatic representations of that set of ideas, and that really shaped the world’s understanding of Hollywood and Los Angeles across much of the 20th century.”

A master of styles including English Tudor, Italian, Spanish Colonial Revival, and modernist, Williams took criticism for not embracing the style of day. Over the years, and against the backdrop of modernist case studies such as Pierre Koenig’s Stahl House or Rudolph M. Schindler’s Schindler House, his versatile legacy took a back seat. “But in a certain way, his wide stylistic range was what made him a really typical Angeleno architect,” explains Hawthorne.

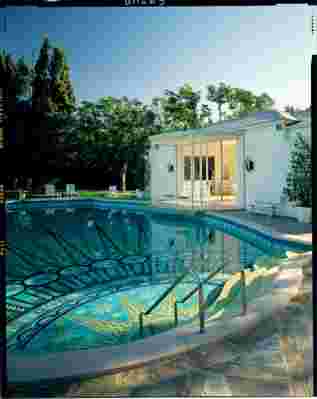

The Zodiac Pool at the William Paley home in Los Angeles, designed by Paul Williams.

According to the Los Angeles Conservancy, Williams designed more than 2,000 private homes in L.A. alone, many of them nestled in the Hollywood Hills and Mid-Wilshire. “[Williams’s body of work] is such an important repository of L.A. domestic architecture, at a period when it was at its most freewheeling and experimental,” says Hawthorne. But Williams’s portfolio stretches well beyond homes. He was involved in the design, and redesign, of many L.A. landmarks such as the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building, the Beverly Hills Hotel, and the First African Methodist Episcopal Church, to name a few. He was also part of the team at Pereira & Luckman, who designed the 1961 space-age Theme Building at LAX.

“His work crosses many stylistic approaches, but what connects it is a certain expectation that a public building should achieve a certain pride in the idea of civic architecture,” says Hawthorne. “Los Angeles, in some ways, was losing that thread in the post-WWII period, but he was responsible, among a very short list of other architects, in keeping it alive.”

The Beverly Hills Hotel.

During the Great Depression, he continued to design homes for the wealthy, like the Tudor Revival–style Atkin Residence, completed in 1929 and tragically ravaged in a 2005 fire. And when post-war population growth brought about a severe housing shortage, he designed affordable housing plans for homeowners and published them in two books. His five-decade career stands as a reflection of the larger economic forces that have reshaped the city in the middle of the 20th century. “There’s no one who worked across quite the same range of skills or styles as he did,” says Hawthorne, “and so it’s all the more important to preserve that variety.”