It’s hard not to pay more attention to our physical realm these days given the fact so many of us are sheltering in place, or are likely to be doing so soon. Anecdotally, at least, DIY home improvement projects are on the rise; if you’re like me, your closet has never been better organized. For many in the design community, however, the rapid spread of COVID-19 has caused them to reevaluate their life’s work, and what it might mean to design for a world that will never be quite the same, especially when it comes to how we gather in and use large public spaces, like airports, hotels, hospitals, gyms, and offices.

As Rami el Samahy, a principal at Boston architecture and design firm OverUnder and adjunct professor at MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning, points out, this won’t be the first time in history that cities and buildings will be reimagined or redesigned in response to an increased understanding of disease: Consider Haussmann’s renovation of 1800s Paris, London’s reconfigured infrastructure in the wake of the city’s 1954 cholera epidemic, and 19th-century New York’s reaction to the squalid conditions of tenement housing. But while the particular lessons of COVID-19 are still very much TBD, a few ideas have already emerged. For one thing, as architect David Dewane of Chicago firm Barker/Nestor points out, “architects are often inspired to come up with fresh ideas during those moments when we’ve got nothing else to do.”

Architect Dan Meis, whose “social suites” for Scotiabank Arena in Toronto make shoulder-to-shoulder fan interaction optional, expects stadiums and arenas to introduce greater opportunities for hand washing and sanitizing, as well as RIFD technology to make purchases.

Open offices were already on the decline before Covid-19, and Dewane, who is perhaps most famous for advocating for and designing anti-open-office “ deep-work chambers ,” hopes workplace leaders will take the best of what they’ve learned from virtual working to help create office spaces that allow for a balance of isolated concentration and productive, meaningful collaboration. “When I graduated architecture school in ’94 we talked about how tech was going to change how we commuted and lived, and that has not been true,” says Lionel Ohayon, founder and CEO of New York design studio ICRAVE , which has overseen health care, airport, hospitality, and workplace projects around the world. “Cities are more popular, people use more paper, commercial real estate is booming while retail is devastated. All this will be tested as we’re forced to work apart. If virtual working is successful, if we’re in fact more productive, it’s going to fundamentally change the value proposition of shared workspace. Not everyone wants to be in a big social playground.”

Almost everyone predicts that public spaces will move toward more automation to mitigate contagion, with COVID-19 speeding up development of all types of touch-less technology—automatic doors, voice-activated elevators, cellphone-controlled hotel room entry, hands-free light switches and temperature controls, automated luggage bag tags, and advanced airport check-in and security. “I don’t see why if I can tell Siri to call my wife, or my remote to cue up Netflix, I couldn’t tell an elevator to take me to the 10th floor,” says Miami architect Kobi Karp, principal at Kobi Karp Architecture & Interior Design , who has worked on projects for the Four Seasons and 1 Hotels. Architect Dan Meis , who has designed sports and entertainment facilities that include the Staples Center in L.A. and Seattle’s T-Mobile Park, expects arenas to introduce far more opportunities for hand washing and sanitizing as well as RIFD technology to make purchases. “Maybe in addition to the metal detectors that have become commonplace in these venues, we may have temperature screening or even some form of UV disinfecting that each spectator is subjected to?” he says. “Although I really hope not!”

Future senior living projects, like this one by firm Amenta Emma, are likely to feature hands-free lighting, curtains, and temperature controls.

Restrooms with doors in public spaces were already on the way out, points out Craig Scully, partner and chief engineer at Fort Wayne, Indiana, firm Design Collaborative , but are likely to be eliminated wherever possible. Designers will increasingly call on antibacterial fabrics and finishes, including those that already exist—like copper—and those that will inevitably be developed. “If five years ago I had a conversation with a convention center about implementing those materials, they might not want to spend the money, but today that’s likely to be a totally different story,” says Scully. Within hotels, Karp also predicts self-cleaning bathrooms as well as pod rooms—smaller modular spaces that can be sealed off from other guests while also offering the ability to be quickly torn down and disinfected.

Certain construction elements already standard in health care may find application in other public spaces, such as reducing the number of flat surfaces where germs can sit, and installing ventilation systems that allow for removing potentially contaminated air from any given area. But health care design will very likely get an upgrade, too. “The biggest thing to come to light during this is the inability for hospitals to accommodate the number of sick people,” says Scully. “So you might see, from design perspective, an ability to make a normal patient room more flexible to increase capacity or be easily converted into an ICU.” Boston dermatologist Ranella Hirsch, M.D. , points out that many existing hospitals, especially in non-urban areas, aren’t a match for modern ailments. “A prime example is the emergency department, by design almost always the first point of entry to a facility and a core flaw in an infectious situation,” she says. “The ER is meant for staging and triage, and always has a place designed for waiting, which is precisely where you want to avoid having highly contagious people.”

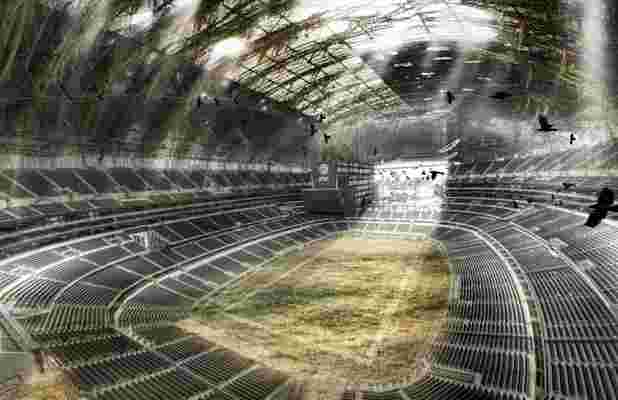

In a 2016 presentation to SXSW, architect Dan Meis predicated the death of the modern stadium and proposed sustainable alternatives to the future of spectator sport.

For their work on the David H. Koch Center for Cancer Care at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, Ohayon's team at ICRAVE worked to eliminate the traditional waiting area by creating alternative “waiting nooks” scattered around the building and relying on RIFD technology to track and alert patients. “This lets patients be somewhere else in the building—the yoga library or somewhere watching a lecture—instead of sitting around on the same floor with other ill people,” says Ohayon. “And if architects and designers help people start to think of public spaces more like home and less like someone else’s space, they’ll be more vested in treating it right—not, like, throwing dirty napkins on the floor—which will make it safer for everyone.”

The ultimate resource for design industry professionals, brought to you by the editors of Architectural Digest

While social distancing would seem to be a necessary, if (hopefully) temporary, action, it’s reasonable to think that concerns about future viruses might encourage architects to design with an eye toward open spaces that enable and encourage people to spread out. Karp wonders if smaller, more expensive hotels will necessarily replace larger ones, even if the model proves less accessible and less profitable. But Rami el Samahy cautions his colleagues against relying too heavily on that sort of mindset: “Giving up on urbanity and density is the wrong solution—after all, we still have a planet to save.” Meis puts it another way. “I don’t think we’ll ever get to the point where we completely avoid public gathering, and it is the magic of sports and concerts, at least, to have that common experience,” he says. “But in all settings, this experience has illustrated that it really is a very tiny world and we are all very connected. We just may have to become a bit less physically so, wherever possible.”