View Slideshow

After earning his architecture degree at Berlin’s Technische Universität in 2004, Diébédo Francis Kéré could have comfortably stayed in Germany. He could have chosen to focus on skyscrapers, museums, and other attention-grabbing public buildings, the kinds of projects that attract the boldest headlines—and, typically, the biggest fees. But instead Kéré returned to Gando, a small town in the largely agrarian West African nation of Burkina Faso, where he grew up as the eldest son of the village chief and the only child in his family to attend school. And yet, unexpectedly, he has achieved renown for his innovative civic buildings there, which combine regional construction materials with 21st-century know-how and provide training and jobs for local laborers.

"It’s my duty to my people," Kéré says. "Architecture has a social role to play. I wanted to start providing my community with infrastructure."

Kéré began to lay the groundwork for his professional focus well before he finished his studies. Back in 1998 he established the charitable foundation Bricks for Gando to raise money for a primary school he envisioned for his hometown. "I started by asking my classmates to spend less money on coffee and cigarettes," he jokes. A few years later, using donated funds, Kéré was able to construct the school—a campus comprising three classroom buildings arranged in a row, separated by outdoor antechambers for teaching and recreation. As with his subsequent projects in Burkina Faso, he employed indigenous materials, most notably clay, which he used to make thick walls, an ancient way to maintain cool interiors even in a climate where temperatures routinely top 100˚F. The buildings feature brick ceilings with long slits for ventilation and are topped by elegant floating roofs that allow rising hot air to circulate out of the interiors. In 2004 the school received a prestigious Aga Khan Award for Architecture and was cited by the jury as "a structure of grace, warmth, and sophistication, in sympathy with the local climate and culture," while the design was further praised for its fusion of "the practical and the poetic."

These days Kéré mostly divides his time between West Africa and Berlin, where his offices are headquartered. With help from donations, Kéré’s firm and foundation promote development initiatives in Burkina Faso, which has one of the lowest per capita incomes of any country in the world. He partners with NGOs on many ventures as well as with architecture departments at German universities to engage students in a variety of projects. Kéré continues to employ large numbers of Burkinabe, having trained them in carpentry, welding, brickmaking, masonry, and painting. "They’re earning a lot of money," he says. "It has changed their future." But, as Kéré notes, much remains to be done. "In many places there is no electricity, and drinking water is a big problem," he says. "We are undeveloped."

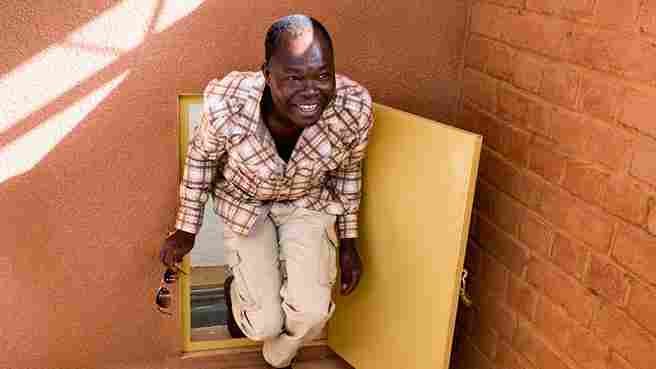

In Laongo, a hamlet near the country’s capital, construction is under way on the Opera Village—a 30-acre campus dedicated primarily to music and theater. Conceived by Kéré with the late German artist and filmmaker Christoph Schlingensief, the complex encompasses a school, a performance hall, a medical center, housing, and more. Kéré is also teaming up with Switzerland’s Accademia di Architettura, where he is an instructor, to build Atelier Gando, a center that will research how sustainable traditional building methods can be adapted for contemporary use.

The impact of Kéré’s efforts in Burkina Faso goes beyond making improvements to infrastructure and providing jobs: Because local people are heavily involved in the building process, they feel a strong sense of ownership and pride. "Normally with public facilities here, nobody’s caring for them," he says. "But people are dedicated to these projects, they feel connected to them. And if something happens, they’re able to fix them."

As Kéré’s practice has gained increasing international attention, he has garnered commissions in Mali, China, the U.K., and elsewhere. He recently won a competition to redevelop the former Oxford Barracks, a onetime British military outpost in Münster, Germany, upgrading housing, commercial spaces, parks, and other public areas in the residential community. Burkina Faso, however, remains the focus of his socially minded work.

"I am really surprised to see the growing interest," the architect says. "People see what I’m doing, and it’s given me energy to keep going. kerearchitectureom

Tour Diébédo Francis Kéré's Opera Village. **