Think Tony Duquette, and certain images spring instantly to mind. Folding screens spattered with giant sunbursts. A coffered ceiling made of plastic serving trays. Chandeliers laden with glistening abalone shells. Then there’s the gilded biomorphic console table that resembles, depending on one’s vantage point, a writhing sea creature or a roller coaster on Mars.

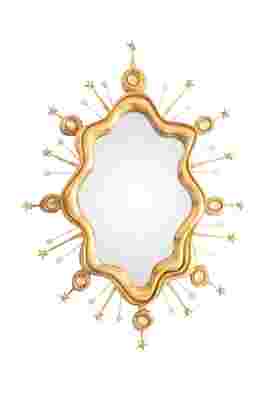

Call it Space Age Baroque—and, according to Duquette’s most ardent fans, it’s the kind of overegging that the world is ready for. “We’re entering a maximalist epoch, and Tony is a maximalist icon,” exults Hutton Wilkinson, a designer of interiors and jewelry who was Duquette’s longtime business partner and has been the keeper of his 24K-gold flame since the latter’s death in 1999, at the age of 85. Sister companies Pearson and Maitland-Smith are in full agreement. In association with Wilkinson—author of the new Abrams salute Tony Duquette’s Dawnridge—the firms are launching a trove of delirious Duquettiana, from reproductions of objects that he created for his own homes to inspired-by furnishings that nimbly channel the master’s bizarro magic.

Some designs were conjured up for clients tobacco-heiress Doris Duke (Pearson’s Duke sofa) and modern-art patrons Palmer and Charles Ducommun (that famous console table, by Maitland-Smith). Others existed as prototypes, such as the Lotus floor lamp. Maitland-Smith is reproducing it in bronze—though, Wilkinson notes, Duquette likely would have used cast resin, one of his go-to materials.

As for the Elsie table, it’s a scaled-up version of a Japanese antique that Duquette’s mentor, the decorator Elsie de Wolfe, gave him as a gift. “My favorite piece must be the hand-painted malachite-and-brass desk. Or is it the Louis XV–style bombé chest entirely veneered in abalone shell?” Wilkinson muses, adding, “Tony used to say, ‘If there were only one abalone shell in the world, wars would be fought over it for its beauty.’ ” maitland-smitom; pearsoncoom