View Slideshow

San Francisco architect John Peterson had already built a successful practice designing upscale homes when he had something of a career-altering epiphany. Working on plans for a large mixed-use development in the city’s Glen Park neighborhood in the early 2000s got Peterson thinking more about the impact architecture could have on improving an entire community. “I became fascinated with that responsibility,” he says. “It led me to ask questions about how our profession was responding to such opportunities.”

Inspired by the tradition of American law firms providing pro bono services for worthy causes, Peterson founded the nonprofit organization Public Architecture in 2002, with the mission of realizing design projects for the public good and with a portion of the work being offered free of charge. After initially collaborating primarily with like-minded acquaintances and peers, the group soon began to expand its outreach, promoting the idea of firms devoting at least 1 percent of their time to pro bono work and helping match them with nonprofits in need of design assistance. “We wanted to shift the culture of practice in our industry,” Peterson says, “and change the way nonprofits and others viewed the role of design as a tool for social change.”

In 2005 Public Architecture took what has become its flagship initiative, the 1% program, to the next level, stepping up efforts to enlist architecture and design studios by launching a website, theonepercenrg, to track commitments and resulting projects. A decade later, the program is a resounding success. More than 1,300 companies have made the pledge, including such industry leaders as Jaklitsch/Gardner, Kieran Timberlake, Perkins + Will, Brooks + Scarpa, and Leroy Street Studio. Each year participants now donate more than 400,000 hours combined, representing almost $60 million in services. With more firms continuing to sign on, the figures are steadily rising, adding an average of $500,000 in volunteered time every month.

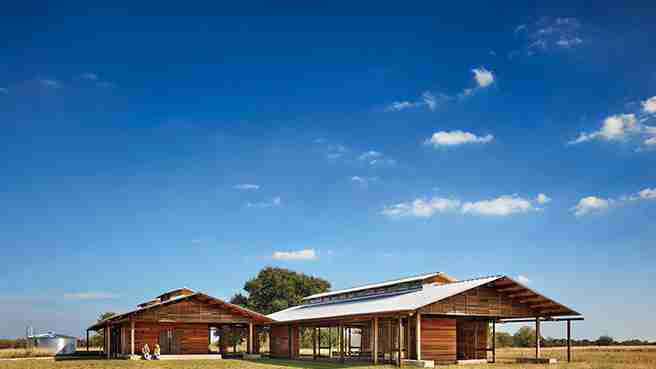

The commitments range from taking part in community design workshops to adding no-cost enhancements onto for-fee projects to designing whole buildings. When the Dixon Water Foundation, which promotes healthy watersheds in Texas, commissioned Lake|Flato Architects to craft a center for meetings and educational events in the northern part of the state, the AD100 firm wanted to go beyond the scope of paid work and develop a truly eco-conscious structure, one that would comply with the extra-stringent Living Building Challenge standards. Opened in November and devised with the help of more than 1,400 donated hours, the Betty and Clint Josey Pavilion utilizes locally sourced materials free of contaminants, generates more energy than it uses, is passively heated and cooled, captures rainwater for toilets and irrigation, and treats its own wastewater. “The idea was to construct a building that actually does good rather than just being less bad,” says project architect Tenna Florian. This type of venture, explains Lake|Flato partner Bob Harris, “allows us to take a step back and think about what can be done at a different level for a different type of client.”

Gensler, a global design powerhouse with 4,800 employees in 46 international offices, estimates it spends 3 percent of its time on pro bono services such as creating pop-up holiday shops for Goodwill and designing a school in Jacmel, Haiti, to replace one destroyed in the 2010 earthquake. Completed for $1 million—with about $96,000 worth of donated services—the school was constructed to withstand earthquakes and hurricanes and has become a model for future rebuilding. “We designed it as a community resource that includes a feeding program, a library and computer room, and a soccer field,” says Richard Walden, CEO of Operation USA, the nonprofit that led the project in collaboration with Honeywell’s philanthropic arm. Without Gensler’s pro bono contributions, he adds, “We probably wouldn’t have been able to hire an architect.”

“When you see people who really can’t afford good design, but you’re able to do it for them, it genuinely touches you,” says Mark Schwamel, an architect in Gensler’s Chicago office and a member of the firm’s community-service committee. “In the end, there’s a different level of satisfaction.” publicarchitecturerg

Click here to see more projects.