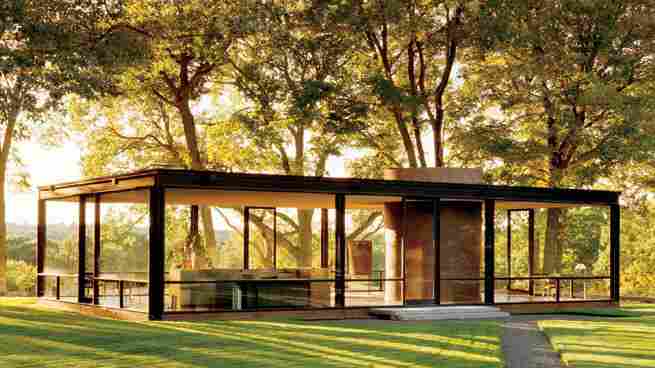

Philip Johnson’s Glass House , built atop a dramatic hill on a rolling 47-acre estate in New Canaan, Connecticut, is a piece of architecture famous the world over not for what it includes, but for what it leaves out. The dwelling’s transparency and ruthless economy are meant to challenge nearly every conventional definition of domesticity.

The residence Johnson built for himself in 1949 suggests a life pared down to Platonic essentials—and triumphantly ready for fishbowl scrutiny. There is something intimidating to people about the restraint such an existence would demand, as if the house itself were silently judging our own messy choices. Still, the appeal of all that self-control, that rigor, is practically narcotic. Why not banish every bit of clutter? For many of us, Johnson’s masterwork is a powerful fantasy.

“It’s my Donald Judd of houses,” says decorator Mariette Himes Gomez . “I’ve never seen anything as perfect. The proportions, the scale, the absolute purity.” Thomas Phifer first visited the property in 1983, when he was working in the office of Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects. “It was a much softer and more delicate building than I imagined, perfectly detailed and wonderfully intimate with its setting,” he recalls. “I remember being particularly struck by how its transparency allows the landscape to flow right through the house.”

Johnson’s design is the architectural equivalent of a brilliantly packed suitcase, with a bedroom, bathroom, kitchen, and space for dining and entertaining all arranged inside a simple rectangle measuring 32 by 56 feet. Yet the residence was built near the end of his love affair with modernism; if you look closely, you can see signs of his budding restlessness with its dogma.

According to Henry Urbach, director of the Glass House (now operated as a historic house museum by the National Trust for Historic Preservation), that rich sense of contradiction, even paradox, is part of the structure’s continuing appeal. “There’s already a very sophisticated irony at work,” he says, “a kind of wit—as if he’s playing along with modernism, all the while preparing for whatever’s next.” For one thing, the dwelling is far from alone on the property; the same year Johnson built the Glass House, he also erected a brick guest quarters next door, and over time he dotted the estate with outbuildings and follies in a wild diversity of styles.

Urbach made his first visit in 2001, when he was running an art and architecture gallery in New York City. Johnson, he remembers, was “very gracious and encouraged me to wander.” Now, as director, he’s able to watch the reaction of others experiencing the house for the first time. Young architects who know it only from books are among the most responsive, he says. “It’s not uncommon for tears to well up in their eyes as they approach the house. There are certain buildings that have such iconic status that you feel as if you know them. But when you actually encounter them in physical space, it’s a different story. People are quite moved.”