Eero Saarinen was born in 1910 in Finland and emigrated to the U.S. in 1923. The architect started his career with an apprenticeship and partnership with his father—prolific Art Deco architect Eliel Saarinen—and went on to become one of the most important designers of the 20th century. Working mainly in the U.S., he created dramatically different structures at each turn in his career, immersing himself in various genres and concepts, making bold choices and executing them with confidence. Thus his oeuvre lacks a signature touch, save perhaps the unifying characteristic of refinement of form. Saarinen’s works are not only architectural treasures but also symbols—they capture an era of technology, of futurism, and of optimism.

Kleinhans Music Hall, 1940, Buffalo, New YorkThis music hall was a father-son collaboration for the Saarinens, executed with local architects F. J. and W. A. Kidd. The building is designed as if it were the body of a string instrument, complete with excellent acoustics, and the façade resembles a parquet floor.

Cummins Inc. Irwin Conference Center, formerly the Irwin Union Bank and Trust., 1954, Columbus, Indiana

The transparent design of the Irwin Union Bank lent a sense of trust—almost to the degree of playfulness—to one midwestern financial institution. Considered one of Saarinen’s most refined commercial structures, the building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2000.

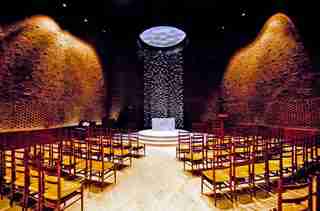

MIT Chapel, 1955, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Commissioned by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, this chapel by Saarinen has no windows, only a perfectly circular skylight directly above the altar. A metal sculpture dangles from the window, reflecting intense light into the otherwise enclosed brick cylinder. The chapel, designed to serve all faiths, is an intensely focused and celebratory worship space.

General Motors Technical Center, 1956, Warren, Michigan

Long before the days of sprawling Silicon Valley offices, Saarinen pioneered the tech campus with his General Motors Technical Center—the hub for the car company’s engineering efforts. President Eisenhower himself delivered a rousing dedication at the structure’s 1956 opening ceremony, describing the center as “a new adventure for frontiersmen.” Saarinen’s space-age modernism reflects the era’s technological innovation.

Miller House and Garden, 1957, Columbus, Indiana

This glass-and-steel house is perhaps Saarinen’s most treasured residential project. The house is modernism at its stately peak.

Milwaukee County War Memorial Center, 1957, Milwaukee

Resembling an unearthed Brutalist bunker, the Milwaukee County War Memorial Center looks out over Lake Michigan. The structure illustrates an extreme end of Saarinen’s broad, expressive architectural range.

David S. Ingalls Rink, 1958, New Haven, Connecticut

Home to Yale Hockey, the Ingalls rink is most recognizable by its huge curved roof. Skaters zip about under what looks like the skeleton of a majestic whale, mysterious and rotund. The building is complete with what could be a harpoon protruding just above the main entrance.

U.S. Embassy, 1960, London

Inspired by the Doge’s Palace in Venice, this was the first building in England constructed specifically as an embassy. Conveying an imposing power, it features a bold geometric stone façade and is crowned with a formidable golden eagle. The building was recently sold to Qatar’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, and the new U.S. embassy is currently under construction across the Thames.

Bell Labs Holmdel Complex, 1962, Holmdel, New Jersey

A massive corporate research facility, this project for Bell Telephone had Saarinen thinking of light and reflection. The monolithic glass structure’s ideal location between two ponds gives it the appearance of a UFO landed on water.

TWA Flight Center, 1962, New York

This JFK terminal was one of several Saarinen projects completed after his death in 1961. This opus magnum took the shape of a compact bird, embodying a ’60s sense of fantasy and science fiction (it would not be out of place as a Southern California Googie pit stop). Requiring, however, a touch more class, the terminal was built to meet the needs of an emerging jet-set elite. Even its most utilitarian parts—the arrivals and departures board, the ticket counter, the waiting area—were designed to emulate the luxurious bridge of a spaceship.

Washington Dulles International Airport, 1962, Dulles, Virginia

A modernist take on a dreamlike classical colonnade, Washington Dulles International Airport is, for many, the gateway to Washington, D.C. Saarinen not only accomplished an elegant and dramatic silhouette in this massive public project, but also developed a new layout that influenced the way future airports were designed. From drop-off to takeoff, Saarinen’s work at Dulles helped to inform decades of air travel ritual.

North Christian Church, 1964, Columbus, Indiana

Comprising a simple hexagon and a massive spire topped with a tiny gold cross, the North Christian Church is a theatrical expression of Saarinen’s imagined intersection of the heavens and the earth. Like many other Saarinen works, the church has a remarkably simple form, yet is enriched by bold choices in configuration and scale.

Lincoln Center, 1965, New York

Saarinen joined a group of famed architects—including Pietro Belluschi, Gordon Bunshaft, and Philip Johnson—to design the Lincoln Center’s complex, with Saarinen working on two: the Vivian Beaumont Theater (shown) and the Library and Museum of the Performing Arts. The impressive names attached to the project gave the cultural center an elevated status in 20th-century Manhattan.

CBS Building, 1965, New York

Saarinen’s foray into skyscrapers proved heavy and dark. The architect hit the heart of the modern office archetype with this blocky form.

Gateway Arch, 1965, St. Louis

Today the Gateway Arch is one of the most recognizable landmarks in the U.S. Saarinen perfected the exact dimensions of this tapered and flattened catenary to create an iconic form. Built on the banks of the Mississippi River, at the starting point of the Lewis and Clark expeditions, the arch stands as a monument for the nation’s westward expansion.